Note: This content was originally featured on Borealia on August 1, 2016. Click here to read the original post and commentary.

Bear Years, Squirrel Years, and Environmental Politics on the St. Lawrence River, 1759-1796

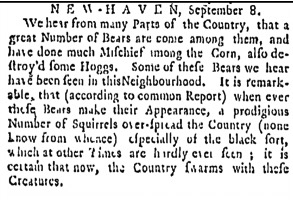

In September of 1759, great armies were on the move through the upper St. Lawrence Valley. Not the military forces under the command of Montcalm and Wolfe en-route to their climactic showdown on the Plains of Abraham, but an army of black bears migrating en-masse southward from Canada into Britain’s Atlantic colonies. During that autumn, newspapers from New England and New York recorded a southern migration of bears, accompanied by an equally mysterious appearance of thousands of black squirrels. Bears were reported in the city of Boston for the first time in a century—a large bear “the size of small cow” was shot on a Boston wharf as it swam across the harbor from Dorchester Neck.

Bears were “spreading mischief” on colonial farms from the New England frontier to the lower Hudson Valley, devouring fields of “Indian corn” and destroying stocks of hogs, sheep, and calves. British army officers bemoaned frequent bear sightings near General Jeffery Amherst’s field headquarters on Lake Champlain. Newspapers printed lurid tales of a bear attacking and eating two children as they picked beans in a field in Brentwood, New Hampshire. One bear reportedly attacked a female colonist walking near her house, but only made off with the “hind part” of her gown. As much as these armies of marauding bears and squirrels vexed Anglo-American colonists, they provided a critical windfall for indigenous hunters residing beyond New England in the Canadian borderlands and the vast St. Lawrence watershed to the north.[1]

Documented “bear years” and “squirrel years” occurred in 1759 and 1796 and they can teach historians about the interplay of ecology and aboriginal treaty making following the British conquest of Canada. France’s former Native American allies pledged neutrality toward the British on the condition that British officials recognize their free mobility through ancestral territory and guaranteed perpetual access to hunting and fishing sites throughout the St. Lawrence watershed, as they did at the 1760 treaty of council at Oswegatchie. More than forty years later, the Jay Treaty of 1794 between the United States and Great Britain reaffirmed the upper St. Lawrence River as the official international boundary between the two countries while reaffirming the rights of indigenous people to freely traverse the new boundary. The latter agreement recognized “Indians” as an autonomous people, distinct from subjects of the British crown or citizens of the United States, and guaranteed their free mobility across the border.

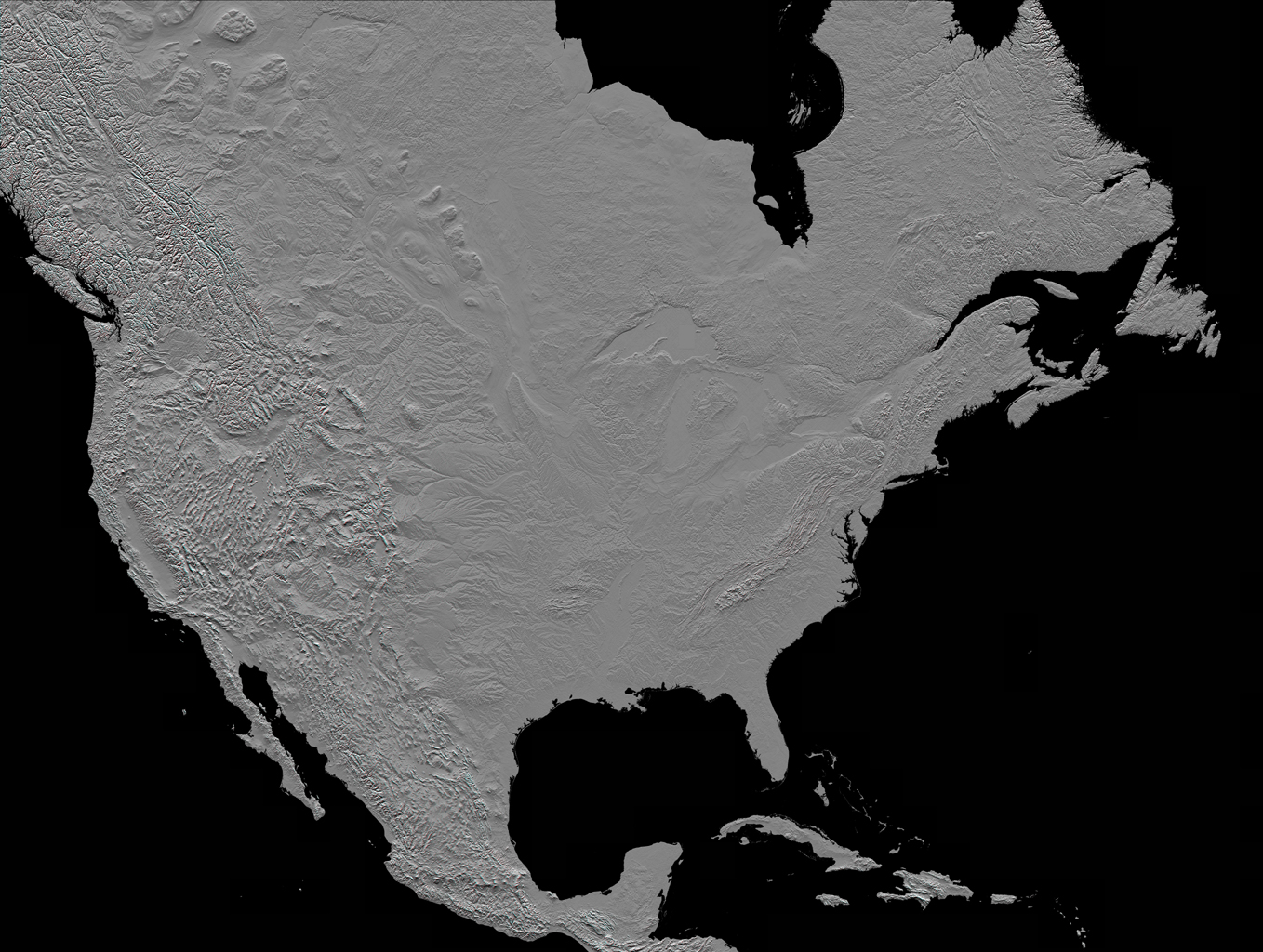

The international border between the United States and Canada distorted the interconnected ecosystems, which bears, squirrels, and their indigenous hunters traversed in order to survive. What Americans now call the “Adirondack” region in northern New York actually marks a southern extension of Quebec’s Laurentian Mountains, physiographic highlands linked through the St. Lawrence watershed. Crucial to the lucrative fur trade economies, indigenous peoples moved seasonally throughout the year, trading at mission villages along the rivers, gathering next at islands in the St. Lawrence to hunt and fish, and eventually into collectively managed hunting territories in the highlands or Canadian shield. Bear years and squirrel years were periodic windfalls for indigenous people, a recurring phenomenon possibly connected with the mast cycles of oak trees. Although United States and Britain affirmed Native mobility rights in the 1794 Jay Treaty largely to protect their own fur trading enterprises, the long term consequence was to permanently enshrine indigenous hunting and mobility rights in an emerging body of international law.[2]

In the autumn of 1796, six months after the Jay Treaty went into effect, the Irish traveler Isaac Weld and a dozen other men boarded a bateau at Montreal bound for the British outpost at Kingston, where the St. Lawrence River opens into Lake Ontario. As his party navigated the river’s treacherous rapids, a hulking black bear “boldly entered the river” directly in front of Weld’s boat. Weld’s companions opened fire, killing the bear as it swam from the riverbank to an island midstream. Such bear crossings were common along the hundred-mile stretch of river between Akwesasne Mohawk territory and Lake Ontario during what Weld’s companions described as a “bear year,” periods defined by heavy black bear migrations south from Canada. Weld commented on the hundreds of “River Indians” gathered to hunt the migrating bears and marvels at the beauty of the “numerous Indian hunting encampments on the different islands, with the smoke of their fires ‘rising up between the trees.’” Although the bears had no trouble swimming across the river, their slower speed rendered them vulnerable to native hunters on shore.

Just like in 1759, Weld also described how an army of thousands of black squirrels crossed the river from the opposite direction, from the newly independent United States toward the newly established colony of Upper Canada. The bushy black rodents swarmed the riverbanks looking for a narrow point to cross the river, destroying as much as two-thirds of settlers’ crops in their path. Weld recorded that the squirrels “swam across in a great mass for three days,” using their tails to propel themselves across the water. Just as in 1759, Weld described a windfall for “River Indians” and an environmental catastrophe for Anglo-American settlers.[3]

Bear and squirrel migrations no longer occur along the St. Lawrence River, but the indigenous communities remain engaged in the transnational politics of environmental stewardship. Supreme Court rulings in the United States (Diablo v. McCandless, 1927; Karnuth v. United States, 1954) and Canada (R. v Sioui, 1990) affirm Native rights to free mobility across the international border and the right to access the hunting and fishing sites where their ancestors waited for the bears and squirrels to swim across the St. Lawrence River. Ongoing environmental policy disputes between indigenous peoples and the governments of the United States and Canada stretch back to the founding of both nations, but by following the trail of bears and squirrels, we can uncover an aboriginal history of the St. Lawrence valley that links the colonial past with a self-determined present.

[1] “Boston.” Boston News-Letter, August 23, 1759; “Boston.” Post Boy & Advertiser, August 27, 1759; “Boston, August 27,” New Hampshire Gazette, August 31, 1759; “We hear from Brentwood, New Hampshire,” Boston Evening Post, September 9, 1759; “Boston, September 8,” Post Boy & Advertiser, September 17, 1759; “Boston, September 17,” New York Gazette, September 24, 1759; “New York, October 8,” New York Gazette, October 8, 1759; “Extract of a Letter from Crown Pointe dated September 28,” New York Gazette, October 8, 1759; “Albany, October 18,” Post Boy & Advertiser, October 22, 1759.

[2] For possible scientific explanations of mass squirrel migrations, see Vagn F Flyger, “The 1968 squirrel ‘migration’ in the eastern United States (Natural Resources Institute, University of Maryland, 1969), Robin W. Kimmerer, Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of Plants (Minneapolis, MN: Milkweed Editions, 2013) 14-15. For the Jay treaty, see Samuel Flagg Bemis, Jay’s Treaty: A study in commerce and diplomacy (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1965); “Enclosure: Points to be Considered in the Instructions to Mr. Jay, Envoy Extraordinary to G B, [23 April 1794], The Papers of Alexander Hamilton, vol. 16, February 1794 – July 1794, ed. Harold C. Syrett (New York: Columbia University Press, 1972), 319–328.

[3] Isaac Weld, Travels through the states of North America, and the Provinces of Upper and Lower Canada, during the years 1795, 1796, and 1797(London: Printed for John Stockdale, 1799), 270-72.